Runway USA

A pilot's guide to destination cities in Flight Simulator

by Charles Gulick

Pocketful of Stunts

It's time you brushed up on your airwork, and this is a fine place to do it. We're not going anywhere this morning, except up. When we reach altitude, you'll put the airplane through some of its paces.

We'll start by taking off a little differently. Make your standard takeoff preparation (10 degrees of flaps and two quick strokes of up elevator, approximating takeoff trim). Rotate normally, but don't take off that notch of elevator as you climb out. Instead, dump your flaps as usual when you're climbing about 500 FPM, and then continue to apply back pressure (up elevator) one notch at a time, with your throttle all the way to the wall. In other words, climb out at an ever steeper angle, until you get a stall warning; then give one notch of down elevator to prevent an actual stall (it's too nice a morning for that, and we're too close to the ground), and continue climbing as steeply as possible—again, just short of a stall.

Go ahead and take off, as described, but as soon as you leave the ground, take and keep a 90-degree view to the left, and observe, along with your instruments, your increasing angle of attack. Unless you're adding up elevator too rapidly, one downstroke should be all you need to kill the stall warning. Try up elevator again; if you get the stall warning again, take off that notch.

As you get toward 6000 feet (where you'll level off) you'll be at your best rate of climb for the environment. Note what your airspeed reads, and also note the pitch indication on the artificial horizon. When you're ready to level off (get your nose down before you start reducing power), you can take an out-front view again.

Straight ahead of you is Flathead Lake, named after a number of North American Indian tribes (most notably the Chinook), who used to deform the heads of their infants to produce an elongated, flat shape, regarded by them as a thing of beauty.

Before you read any further, get straight and level, with your elevator in neutral position at 6000 feet. Use whatever power is needed to hold that altitude.

During the following maneuvers, use Flathead Lake and the geography that surrounds it as a reference area. After each maneuver, turn so that you are flying toward or over a portion of the water. That will help you in the maneuvers, and in judging how well you did them, as well as give you something interesting to look at. You can get into whatever position appeals to you as you climb back up to 6000 feet. (If you prefer a little less realism, but shorter execution time, you can go into the Editor for a moment and save your 6000-foot straight-and-level mode just as it is; that way you won't have to climb back up each time. But if you're a realist, forget the Editor and climb back up each time.)

First, we'll do a power-off stall. Here (for those of you who didn't learn it with me in 40 Great Flight Simulator Adventures) is how:

Power-Off Stall

- Close your throttle completely. (In this and all cases, do not use the unrealistic “instant” cut or full throttle keys; decrease or increase power using the normal throttle control keys.)

- Use up elevator to achieve a slightly nose-high attitude.

- Steadily add more up elevator, trying to maintain the nose-high attitude.

- Ignore the stall warning and continue adding up elevator until the nose drops abruptly (this is the stall).

- Apply down elevator until the indicator shows (approximately) operational neutral position.

- Add full power until the horizon comes into view again.

- Reduce power to your normal cruise setting.

- Re-establish straight-and-level flight.

- Climb back to your original altitude for your next maneuver.

The most exciting way to witness this maneuver is to perform the whole thing until your nose drops, while looking 90 degrees out the left or right side windows. You'll see evidence of your original nose-high attitude in the bend of the side horizon. Try to keep the bend until the wing, having lost all lift, stalls (and you'll know for sure when that happens). Then, as your plane goes into a dive, take a front view so you can watch for the horizon or, if you like, keep the side view and use your artificial horizon.

Next we'll do a power-on stall. You already know something about that maneuver, because at the beginning of this flight we got as far as the stall warning during your takeoff and climbout.

Here's the complete procedure:

Power-On Stall

- Add full power.

- Use up elevator to get into a climb.

- Continue back pressure (up elevator) to steadily steepen the climb (try to keep horizon invisible under your nose).

- Ignore the stall warning until the aircraft's nose drops abruptly.

- Return your elevator to its (approximate) operational neutral position (to recover from the stall).

- When the horizon comes into view again, reduce power to your normal cruise setting.

- Re-establish straight-and-level flight at your operational neutral elevator setting.

With the power-on stall, you are likely to net an overall gain in altitude of 300 to 500 feet. Again, it's useful to execute it while looking out the side of the airplane, or taking alternate views forward and to the side.

For your next trick, practice a few rolls, the way you learned to do them in Flight Simulator Co-Pilot.

In one roll, stay on your back awhile before you roll out. (I'm not going to repeat the roll procedure in this book, because if you haven't read Co-Pilot, you tried to skip a whole semester, and you're just a real danger up here by anybody's standards.)

Now, the loop. Aye, here's a classic for you, and one of the most fun stunts you can do in the simulator:

Loop

For this maneuver you need more altitude, so first climb to 7000 feet (and, for practice purposes, save your mode when you get there).

- From straight and level (minimum 4000 feet AGL), apply full down elevator.

- Wait for the airspeed indicator to pin at maximum.

- Smoothly apply up elevator until the indicator is at about its three-quarter position.

- When you see only sky, apply full throttle.

- Take a side view until you are nearly inverted.

- Switch to a front view.

- When you see earth or lake only (you're then on the downside of the loop), cut throttle completely.

- When you see horizon again, return your elevator to neutral and your throttle to its normal cruise setting.

As you try to get the hang of this, analyze what you're doing and why. First, you need all the speed you can muster to climb up steeply and turn over on your back. That's why you dive first—to pick up the speed.

You want a nice round loop. Don't rush your up elevator; apply it smartly and smoothly, but not abruptly.

As your airplane's angle of attack increases to the point where you're climbing so steeply that all you see out front is sky, you push the throttle to the wall, because you need all the power you can get to continue to climb.

You take a side view next, because that's the only place where you can get a clue as to your relationship to the earth; the blue sky gives you none. When you can see you're almost upside down, you know you're just about at the top of the loop, and you'll shortly be descending. You look out front again, and watch for the ground to fill your windshield. Then you know you're on the downside of the loop, so you cut your power completely, because the airplane will pick up plenty of speed without any assistance from the engine.

Then, when you see some horizon again, you're back to a more or less normal condition, so you normalize your controls and make whatever adjustments are needed to resume straight-and-level flight.

(If you have an unfortunate contact with something other than air when you first attempt the loop, don't be discouraged. Try again with some altitude to spare, say at 5000 feet AGL—that means an altimeter reading of 8000 feet here over Flathead Lake—until you get the hang of it. It takes some practice, as does anything worth doing.)

It should be mentioned that the procedure described for looping the simulated Cessna and Piper is not very realistic. The entry speed required (from the initial dive) is higher than that in an actual aircraft. Theoretically, an extra 30 percent of speed should normally be enough to execute the loop (see the book Roll Around a Point by champion exhibition pilot Duane Cole), but no way will our Cessna or Piper climb and turn over on its back starting with that entry speed (at least in my experience). Therefore, we need a lot of altitude, because we lose a lot of it diving for speed.

Now that we're up here, and we're into loops, here's another stunt for your repertoire. It involves simply a half-loop and a half-roll, and is called “The Immelman,” after World War I German ace Max Immelman (though there's some argument as to whether he ever executed the maneuver, at least in a dogfight).

To do it, do a half-roll at the top of your loop, a hair before you're inverted (checking this with a side view, as in the full loop, but quickly switching to a front view so you can control the rollout). This is a very advanced maneuver, and when I get really expert at it I'll let you know.

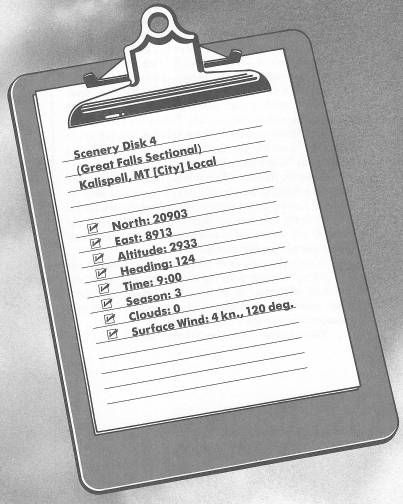

Practice any or all of the foregoing stunts to—as the expression goes—your heart's content. Then follow a generally northerly direction back up the lake—hugging the west shore—to Kalispell Airport and your landing on Runway 13. If you need to, you can pick up a radial to fly toward Kalispell OMNI, frequency 108.4. But as you can see on your chart, the airport is about eight miles southwest of the station, and a big bend of the Missouri River points straight at it. Your best bet is to use your eyes, and remember the airport elevation: 2933 feet.

Table of Contents | Previous Chapter | Next Chapter